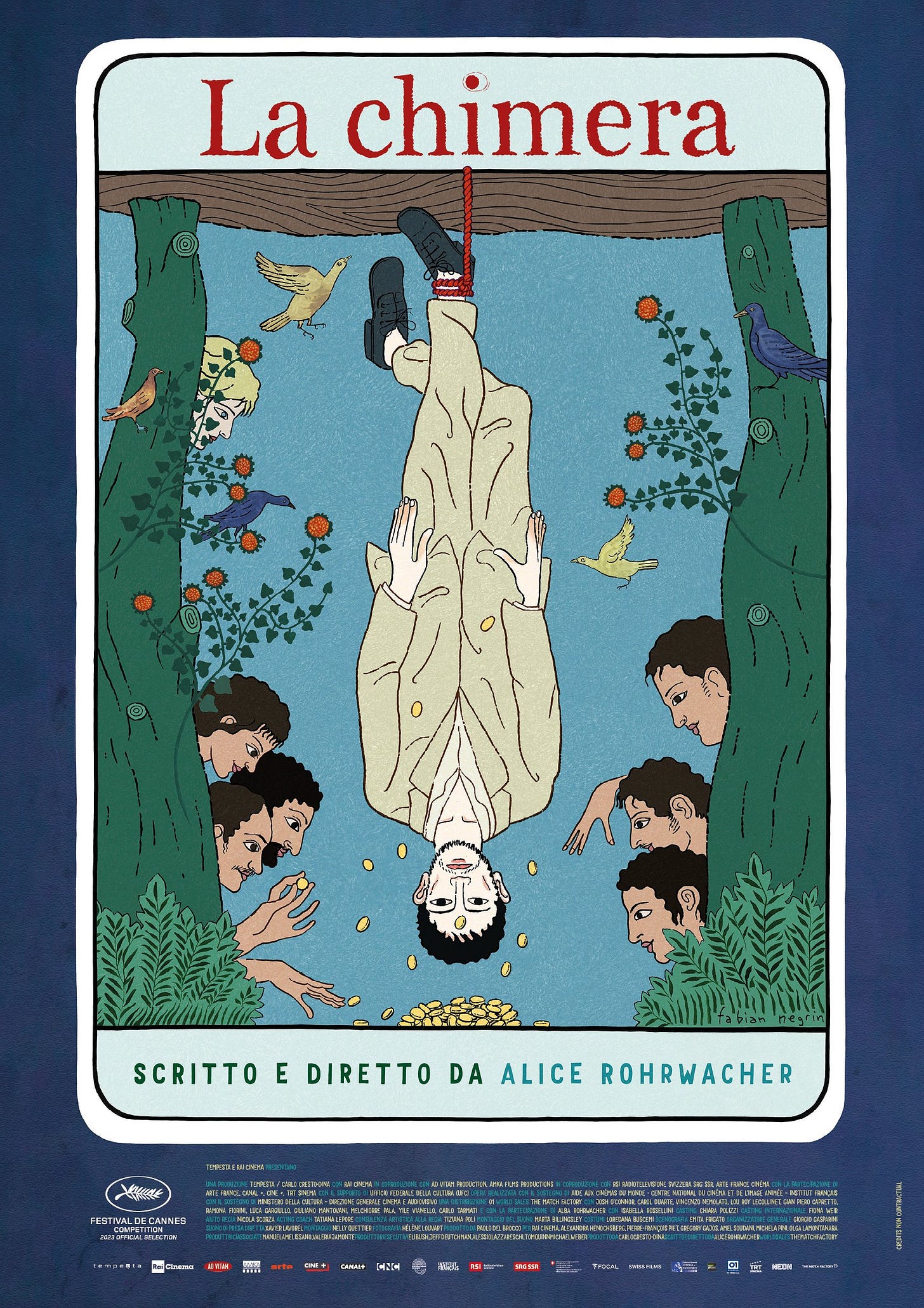

En route across the Atlantic, Athens to Atlanta recently, I watched movies in between stretches of reading, trying to stay awake. The only good one I saw was La Chimera (2023), an Italian film co-written and directed by Alice Rohrwacher, and starring Josh O’Connor, Carol Duarte, and Vincenzo Nemolato. It’s a charming story that floats languidly between caper, romance, Italian shtick, and magical Orphic trek to the underworld. It’s hard to categorize, but a delight to see. And while the mythical, magical elements of the story are ambiguous enough to provoke questions of interpretation, they don’t jar. Minor spoilers will follow (although, in my view, you can’t really spoil good art).

The movie follows the character of Arthur (Josh O’Connor), an Englishman living in Tuscany who has, at some point in the past, lost the love of his life, Beniamina (Yile Yara Vianello). She resides now only in the grave and in his memories. Arthur, consequently, has been reduced to a state of aimlessness, as his only real desire is reunification with Beniamina. Arthur’s only other love in life is archeology, but, we’re told, he never pursued it enough to go legit. Instead, he’s taken up with a band of misfit grave robbers, and they spend their time finding and picking through old Etruscan tombs, selling the “grave goods” to Spartaco, a local dealer of illegally acquired antiquities.

It turns out that the key to this ragtag band’s success is a curious ability of Arthur’s. With a divining rod, he can mystically sense the presence of tombs: the places where souls rest, the presence of apertures between our world and the underworld. This makes him an absolute cash cow for his friends, those louts who refuse to work a real job and don’t mind desecrating sacred spaces.

Against this is the new girl in his life, Italia. Italia serves as a maid for Beniamina’s mother, Flora (Isabella Rossellini), who remains hopelessly devoted to Arthur and convinced of Beniamina’s eventual return (either unaware or in denial about Beniamina’s death). As Italia slowly becomes grafted into Arthur’s life, she finally comes to realize how he and his friends make their money. She is aghast. She curses them.

The curse of a good woman may just be a blessing. This is the turning point for Arthur, who comes to realize that, as Italia says, the beautiful artifacts he is uncovering in tombs are “not meant for human eyes.” They have been placed there for the souls who rest, not for the living. He turns his back on his band of grave robbers at the moment when they are finally going to make a life-changing payday.

While a symbolic interpretation of the movie would bear fruit, what I want to focus on is a specific kind of development in the character of Arthur that occurs during the second act. At the start of the film, Arthur is jaded. He is searching for Beniamina, but only halfway, using the divining rod mainly as a way to serve his appetite to dwell under the earth, away from human eyes. He is angry, self-absorbed, and unconcerned with the moral bankruptcy of his choice to spend his time desecrating tombs and robbing the graves. Both morally and emotionally, he is at death’s door.

But Arthur isn’t totally bereft of feeling. He loves the archaic, the Etruscan age and the artifacts he and his compatriots uncover and sell. His friends say this about him, but more importantly the movie finds him secreting away certain trinkets from the graves to keep for himself. Not for financial gain, but merely to behold, to gaze at with a certain longing and wonder. The eventual change in Arthur is born out of this love, but that birth is “midwifed” by Italia, when she declares that grave goods are not meant for human eyes. Italia, as the obvious symbol of conscience, country, and birth giver herself (as she has two children) doesn’t merely awaken in Arthur a sense of cold duty. What she awakens in him is a stronger sense of love.

In

’s The Ethics of Beauty, Patitsas stresses the point that goodness follows beauty, or as he also puts it (transposed to the key of inner sentiment), agape follows eros. The idea is meant to be that the natural way to cultivate moral sentiment in human beings—concern for others out of empathy, a sense of duty and conscience—is first to cultivate erotic sentiment in those human beings—love of others that is not necessarily romantic (as it is often taken necessarily to be by modern audiences) but, as Patisas puts it, “love that makes us forget ourselves entirely and run towards the other without any regard for ourselves” (Patitsas, 55). Erotic love is fundamentally a pursuing love, and that pursuit requires a lack of self-love or even really any keen awareness of self. On Patitsas’s view, once a person has cultivated strong, healthy erotic attachments, they will naturally have the kind of empathetic concern for others and lack of self-directedness that’s constitutive of agape. Beauty draws us out of ourselves into a life of Goodness.This, it seems, is what we see in the character development of Arthur. It would be easy to interpret Italia as awakening a sense of duty in him if we didn’t watch closely, but it’s obvious that this isn’t what’s happening. As Italia curses Arthur and his friends, they immediately find the biggest and most archeologically important haul of their career. Not a tomb, but a shrine, to an unknown Etruscan deity. The statue of the goddess at the heart of the shrine is fully formed, and its beauty captures Arthur. But quickly we see the rift forming between Arthur and his friends, because while the rest of them want to rip the statue apart and haul it out in pieces, Arthur’s love for the archaic won’t allow him to consider anything so barbaric. As they’re arguing, they think the police arrive and they run away with only the head. Later, after they discover it was Spartaco’s henchmen who spooked them, they seek to instead sell the head to Spartaco, making a fortune. Arthur can’t get Italia’s words out of his head: “You’re not meant for human eyes.” She has awoken his eros. He throws the head into a lake.

What this all brings to mind for me is a theme I’ve been stewing on here over the last few months, namely that of “self-forgetting”. To briefly summarize some of what I’ve said so far, in the first article in what has become an unintentional, ongoing series: I noticed that binging, scrolling forms of consumption wherein one loses oneself in “the feed” are limitless, diffuse, and driven ultimately by what Christian church fathers called “self-love”—the desire to experience pleasure and avoid pain. The antithesis of these activities, I argued, is communion, that activity wherein we really give time and attention to a particular being—a person or object worthy of attention—and thereby grow close to someone. Communion does hold certain pleasures, but it requires openness to pain, struggle, effort, sustained attention, vulnerability. We have to actively resist the temptation not to choose isolation and ease over communion and struggle. In the following article I picked up on a thread from

’s writing that ties binging-scrolling activities to the spiritual state of lethargy, wherein one achieves oblivion and self-forgetting by way of inactivity. For many, that state of oblivion is desirable. It is the distinctive kind of self-forgetting that disrupts the possibility of pain, but which also disrupts the possibility of meaning, or pleasures worth having. I pointed out in that article that we can also achieve self-forgetting through activity, through work or play that is absorbing.How to Lose Yourself, and How Not to

I keep coming back to the American Time Use Survey, which shows that the amount of time we spend with friends per week has dropped in just the last decade—from 6.5 hours per week down to just 2.75 hours per week. For decades in American life it was normal…

Active vs. Passive Forgetting

I recently wrote about the notable difference between two kinds of “self-forgetting”, namely the kind induced by screen-based activities like doom-scrolling or binging and the kind we experience when we immerse ourselves in something truly beautiful. In both instances, for a short while, we characteristically lose all sense of self-awareness or concern …

What has been clearly missing from anything I’ve thought or said about communion—i.e. the good type of self-forgetting—is the role that love plays in it. Patitsas, following Allan Bloom, continually refers to eros as “love’s mad self-forgetting.” This is to pick up on a Platonic theme from the Phaedrus in which Socrates characterizes erotic love as a kind of madness, particularly the madness that is the cause of robust, active pursuits—of people, of ideas, and in general of things in which we can see Beauty. This makes love—and in particular eros—the natural foil to lethargy. The latter is self-forgetting induced by absolute passivity. The former is self-forgetting induced by the most fervent activity.

On Patitsas’s “Beauty First” account of ethics, Beauty (corresponding to eros) leads to Goodness (agape), which leads finally to Truth (philia). This is to say that the natural progression of development in our relationship to these transcendentals is to fall in love with Beauty first. In our pursuit of Beauty, we forget ourselves and so are prepared to act for the sake of the other, which is constitutive of virtuous deeds. This leads us into true friendship with God and others, the life of truth and peace for which we were designed. Patisas’s account makes sense of why active self-forgetting (through eros) is so much more rewarding than passive self-forgetting.

We see the relationship between Beauty and Goodness (eros and agape) that Patitsas describes depicted exactly in the story of Arthur. At the beginning of La Chimera, Arthur is clearly mired in lethargy. He has almost no drive to pursue anything in particular. He falls into robbing graves because it’s the easiest thing available to avoid work (pain) and pursue time with friends (pleasure), while at some level still allowing him to search for Beniamina (the one spark of communion he’s still entertaining). But Italia’s remonstrance of their robberies, along with Arthur’s catching sight of a truly beautiful ancient face in the statue of the Etruscan goddess, awakens his eros for the past. His love becomes too strong to stay inactive. He forgets himself in it and as a result his moral sensibility awakens. He can’t offend against the statue by selling it.

Another author that helps make sense of this story is Talbot Brewer, in his essay “An Economy of Life.” Brewer, focused here on Plato’s picture of love as presented in the Symposium and Phaedrus, develops the opposing ideas of Economy of Life and Economy of Death. On the interpretation he develops, Plato’s view of eros is that it is a response to the possibility we see in someone or something. We catch a glimpse of what that person or thing could be—its true form, to put it in crassly Platonic terms—and fall in love with the thing on account of the splendor imparted to it by that form. The desiring aspect of love is the urge to help birth (or at least midwife) the best version, the one truest to the form, of the person or thing we love.

This picture of eros that Brewer, interpreting Plato, paints, gives rise to what he calls an “Economy of Life”, an organic system of intergenerational organic relationships in which ideas, virtues, traditions and so forth are handed down through erotic birthgiving. This economy, as Brewer points out, is on exhibition in the very account of love offered in the Symposium, “in which Plato tells us what Apollodorus tells a curious companion about what he told Glaucon a few days before about what Aristodemus told him was said many years ago by those gathered at the house of the dramatist Agathon, who, amid the eating and drinking, had decided to tell each other what they thought they knew of love” (Brewer, p.1). An Economy of Life is one in which all involved are continually moved to nurture the growth and development of the others. It is an Economy of Communion, one that is intrinsically directed towards relationships of love, union, and maturation into the Good. It is active, and the people who enter into it will experience the kind of active self-forgetting that we’ve been thinking about in this informal series.

The Economy of Death, by contrast, is what occurs when the natural (i.e. living and organic) mode of relationship is exchanged for the pursuit of pleasure, the avoidance of pain, and the absolutization of monetary gain. To illustrate the concept of the Economy of Death, Brewer points to Lysias’s speech in the Phaedrus, a speech condemning eros but which is given (ironically) with the sole motivation of gaining sexual access to the listener. As Brewer points out, Socrates’s critique of the speech attacks both its form and content, highlighting the fact that an enemy of the erotic—someone directly attacking the Economy of Life—will be unsuited to give a speech with any organic unity. Lysias’s speech is more like a dead thing. His language, like Midas’s statues, has been turned inert by his pursuit of pleasure outside the scope of true love.

The dual Economies can be seen at work clearly in the story of Arthur. At the beginning of the story, Arthur interacts with others almost solely in The Economy of Death. His friends are interested only in pleasure and money. He acquiesces. There is no meaning here. Their work is intrinsically culture destroying. They don’t make anything; they add nothing to and mature nothing in their community. They’re merely subsisting off of the detritus of graves. A literal economy of death.

As Arthur is cursed by Italia, experiencing some pang of healthy shame, and immediately beholding Beauty in the statue he discovers moments later, he is thrust into the Economy of Life. Except, in this case, the statue already approximates its true form. Arthur can’t bear to see that form offended against, so he obscures it.

There’s a lesson in these reflections on two kinds of oikonomiai, one of life and one of death. The lesson is for anyone who finds himself exhausted by life and alienated from his world and his peers. We are always weaving our life’s threads into one or the other of these tapestries. It gets harder and harder to participate in life-giving relationships as our broader culture cedes its territory to what makes easily entertains and makes money, i.e. as our culture becomes more deathly in its broader character, like one of Midas’s statues.

But it isn’t impossible to choose life. Even a mostly dead soul can be brought back from the brink. All it takes is a genuine love, and a genuine theophany. These are gifts. What we need are eyes to see and a heart to receive. This may mean putting down the damn phone. Or it might mean a friend who loves us enough to curse us for making or saying something crass and impious.

In today’s gospel reading for the divine liturgy (in the Orthodox Church), we read the story from St. Matthew’s gospel of the Roman centurion at Capernaum who came to Christ to plead on behalf of a servant who was lying “at home paralyzed, dreadfully tormented.” It’s the centurion’s combination of faith and love—his care for his servant and his expectation that Christ can reawaken the man and bring him from a living death back into the Economy of Life—that is surprising enough even to Christ to receive comment: “Assuredly, I say to you, I have not found such great faith, not even in Israel!”

The ending of La Chimera pushes the dialectic of love and lethargy, life and death, a bit further. It seems that once Arthur awakens to the Economy of Life, he will settle down with Italia and become an honest man. But he can’t drop his search for Beniamina. After a brief trist with Italia, Arthur returns to the underworld. The movie’s ending sees Arthur and Beniamina reunited, leaving the viewer to interpret the meaning.

My reading is that the Economy of Life is really something of a via media. On the one side is the Economy of Death, in which one loves nothing and pursues only pleasure and the avoidance of pain. But on the other side are inordinate loves, as for example when one seeks katabasis—descent to the underworld—because one’s greatest devotion is to a dead person. Arthur has a living, breathing, good woman who clearly wants to build a life with him. But he can’t get over his love of Beniamina. You can’t find the union that love desires with a dead person, though, unless you die yourself. So these inordinate loves lead one out the back door of the Economy of Life to a place of death again. This is where La Chimera seems to leave Arthur, his character having been drawn out of the Economy of Death, into that of Life, only to find himself once again sinking into the underworld.

The concept of “inordinate loves” is best exemplified in La Chimera’s repeated tagline, “not meant for human eyes.” When Arthur and his friends open the doors of the Etruscan temple, presumably sealed some 2,500 years, Rohrwacher captures a shot of the frescos on the wall undergoing a kind of rapid fossilization and opacification. Before the door opened, there was life. These observers—even the loving, erotically charged Arthur—have brought with them death. In an age where people largely interact through the medium of an internet awash with AI trash, I think we can use the reminder that not everything is meant for human eyes.

References

Brewer, Talbot. “An Economy of Life,” Raritan 41:4, 1-18.

Patitsas, Timothy. The Ethics of Beauty, St. Nicholas Press, 2019.

I am a full time high school educator and parent. In order to do the writing I do here, I work on this publication between 4:00-5:00am most days. I write because I love to, and I won’t put a paywall up on my work. If you appreciate what you’ve read, it would encourage me if you left a note or shared it with a friend. If you’d like to show appreciation with monetary support, please consider giving to my church’s second building fund by clicking below, selecting “Give to Second Campus,” and entering an amount.

this is such a fascinating and beautifully written piece! love the various ideas and sources you draw from in analysing the two turns in arthur's trajectory - first in response to italia's rebuke, and then in the final moment of the film where he reunites with beniamina. and really enjoyed reading about your thoughts regarding communion as a something requiring active participation, attention and vulnerability; in contrast to other habits which can be so isolating but therefore mindless and easy in a way. will definitely be adding the ethics of beauty and brewer's essay about economy of life to my reading list!

the concept of "economy of life" and "economy of death" in relation to the film, is really fascinating. especially how i think "economy of life" is also strongly depicted in the commune that italia later creates in the film.