Why Write?

Even if no one will read it and no one is sure what's AI and what's human

I wrote recently about my “close call” with death. A drunk driver veered into my lane from the oncoming traffic. We collided head-on, going roughly 40-45 mph. He wasn’t wearing his seat belt. I was. For him, it was the end. For me, it was a bracing experience, and one I’ve run through in my head every day since.

The most frustrating aspect of the experience is not the accident itself, losing my vehicle, replacing it, the physical pain that resulted, nor even the fact that the other driver’s BAC was pushing three times the legal limit. The most consistently frustrating part has been the forced intimacy with the many arms of the what I’ll call the Care Committee of the State. These are firefighters, EMTs, doctors, nurses, sheriffs, DPS, DOT, insurance adjusters—all the departments and personnel you have to stop and talk to or, much worse, call on the phone for weeks on end when something like this happens.

It’s bad form to say anything firefighters, sheriffs, nurses and some of these others that doesn’t honor them. I’ll say up front that I do honor their work. I’m certain it’s hard, largely thankless, and exhausting. I’m thankful to them.

But, I’m lumping them in with the insurance adjusters all the same, because there’s a kind of total experience I’ve been reflecting on that involves them too. In almost two months of talking to the Care Committee, not one representative of any kind has set aside the business of the moment to acknowledge our shared humanity and say something along the lines of, “Hey, that’s a hard thing you experienced. I’m sorry.”1 This trend of inaction began at the scene of the crash, with the firefighters, EMTs, sheriffs, and highway patrol—there were a dozen or more such officials present. No one asked me how I was doing. They asked things like, “Are you injured?” “Do you want to go to a hospital?” “What is your address?” “Can I see your drivers license?” “Can you give me a description of what happened?” “So, you’re denying medical attention?” They didn’t say, “You’ve been in an accident where someone died; this is going to be a lot to process.” They said, “So, he actually passed away, so we’re going to need you to stick around to answer questions for DPS.” No one looked me in the eye.

That trend has continued over weeks as I have made literal hours of calls trying to locate my car—no one called me to tell me where it had been towed or what would happen to it now that it was totaled—to figure out whether there was an accident report or when it would be released, to try to find out whether the other driver had insurance, to try to discover why the accident report wasn’t available when the DOT said it would be or why the doctor’s office wouldn’t talk with the insurance adjuster. These people are (mostly) good at their jobs, whether those are about caring for the body or overseeing the distribution of funds and information by large organizations. The problem is that none of their jobs have anything to do with being a complete human being, as opposed to being in possession of a human body or a human bank account or humanly identifying information. But trauma, grief, and anxiety are human experiences. It’s dehumanizing to feel these so deeply and be met by the de facto Care Committee, only to be treated as something inhuman, as some unholy amalgamation of flesh, bones, organs, and bank accounts with a collective legal status. They aren’t rude about it. They’re just doing their jobs. And that’s the problem.

I’m thankful for these people. They’re good, nice people, who are helping, in the way they’re able. The whole process is alienating.

As the title suggests, I’m trying to write something about writing here. So, what does any of this have to do with that? In my mind, at least right now, quite a lot. My mind aside, thinking about writing requires thinking about humans. Writing is something we do. So I’m going to continue thinking about us for a moment more before returning to the thing I really want to weigh in on.

Ponder for a second, how did we even get to this point where we’re all driving cars around, and someone veers into yours and you hit each other and they die and then the various arms of a mechanized bureaucracy force you to do all the leg work for them while you’re the one struggling through the grief of what you just experienced? We wouldn’t design things this way if we tried to make an ideal system. But in our system it happens frequently.2 So, how did we get that seemingly accidental result? One simple but obviously true partial answer: we got here by prioritizing efficiency. Traveling by foot, hoof, and even rail was not very efficient when compared to combustion engine and wheels. So we built roads and put the faster, more efficient death machines out there. So car insurance companies appeared to help people with deal with the crashes (and their newfound dependencies on driving). The state needed a way of regulating all the traffic, so the DOT, separate from law enforcement, which has also gotten larger and more fragmented. Etc. One result? In 1800 when someone got in a really bad horse and buggy accident they didn’t have to sit on hold on the phone for weeks afterwards with three state agencies, two insurance companies, and four adjusters to try to get their affairs sorted. Presumably they actually only had to talk to people they already knew because the sphere of their interactions was largely constrained to the local.

Efficiency isn’t all bad. It has benefits. But it also has consequences. At the level of the whole society, it removes friction and reduces certain risks, and it certainly helps some individuals out in ways that aren’t always easy to detect. But at the level of the individual there are real costs. We feel these costs, because trying to engineer efficiency in a society is really a way of trying to turn that society into a big machine, and individuals are not meant to be parts in a machine. If we want proof of this, we just need to remember the horrors of working in textile factories in the early days of industrialism, the modern day equivalent of which is underpaid, traumatized “content moderators” employed by all of the AI and social media giants. The mechanization and industrialization of the whole has always led to the exploitation of some and the alienation of all.

There’s a Fleet Foxes song that I used to resonate with, “Helplessness Blues.” One of the lines that always stuck out says

I was raised up believing I was somehow unique

Like a snowflake distinct among snowflakes, unique in each way you can see

And now after some thinking, I'd say I'd rather be

A functioning cog in some great machinery serving something beyond me.

Released in 2011, this resonated with Millennials like me who were raised on Disney movies (on repeat on VHS) telling us to follow our dreams because we were all perfectly unique snowflakes. Each of us got older and realized, “I’m not so special,” and there’s actually something comforting about being a part of something bigger.

But the nature of the bigger thing one is a part of really matters too. Robin Pecknold of Fleet Foxes opts for a machine. I say, “No, thank you.” If we’re offered a choice between the existentialism of Disney princesses or the de-humanization of mechanized industrialism, we ought to search for some third way.

The problem with both the existentialist and industrialist visions of life is that both deny any robust, stable picture of humanity. The existentialist says there’s nothing to humanity except our ability to shape and mold ourselves in whatever way we see fit. He denies any sort of telos or vision of the good life for humans and leaves it up to the individual to determine what the aim of his own life is going to be.3

The industrialist, on the other hand, posits a telos, but not for the individual. It’s a goal at the level of the whole society, and the goal is infinite economic growth. To feed the growth? Technological innovation.4

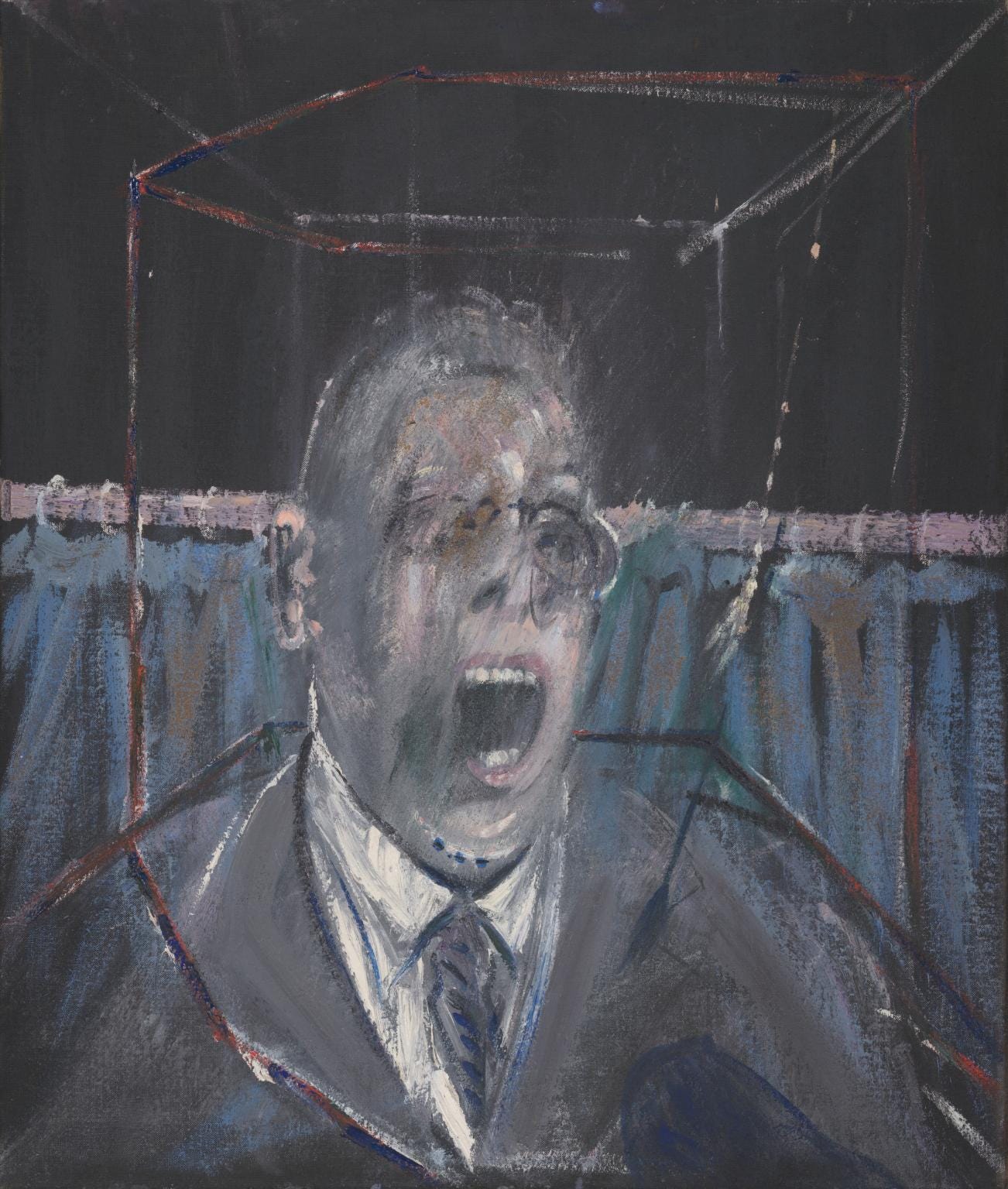

Existentialism and industrialism—two ideologies that are formative for the culture we currently occupy—are both humanity-denying. They lead to a deep experience of alienation, both from ourselves and from those around us.

That experience—alienation—is the one I keep coming back to in these reflections. It’s the same experience I encountered with the Care Committee of the State. Alienation is the phenomenological counterpart to fragmentation: when relationships break apart or stop functioning the way they should, alienation of one from another is the felt result. When a person begins to break into disparate, competing parts, alienation of the self is the felt result. Alienation is what de-humanization feels like.

This experience, the feeling of being out of touch, out of place, and unable to fully understand or navigate one’s reality is not new. People have always struggled with alienation, with unhealthy distance from each other and from their own hearts. St Augustine of Hippo, reflecting on possessing the incredible powers of a working human mind, writes

A great admiration rises upon me; astonishment seizes me. And men go forth to wonder at the heights of mountains, the huge waves of the sea, the broad flow of the rivers, the extent of the ocean, and the courses of the stars, and omit to wonder at themselves… (Confessions Book X, section 8)

To some extent, alienation is driven not by external forces, but by the internal avoidance of oneself, the desire to become absorbed in a pretty sight or sound rather than to “wonder at” oneself, to sit with one’s own thoughts and get in touch with the inner chambers of the heart, which turns out to be both harder and—for reasons we’re all familiar with—scarier.

However, while timeless, this experience of alienation does seem to be getting worse as modernity advances. In the 17th century the great polymath and proto-existentialist Blaise Pascal, reflecting on the nature of humanity and the condition of his fellows in his own day, has this to say about the problem of alienation from oneself:

I have discovered that all the unhappiness of men arises from one single fact, that they cannot stay quietly in their own chamber. A man who has enough to live on, if he knew how to stay with pleasure at home, would not leave it to go to sea or to besiege a town…

The only good thing for men therefore is to be diverted from thinking of what they are, either by some occupation which takes their minds off it, or by some novel and agreeable passion which keeps them busy, like gambling, hunting, some absorbing show, in short by what is called diversion. That is why men are so fond of hustle and bustle; that is why prison is such a fearful punishment; that is why the pleasures of solitude are so incomprehensible. That, in fact, is the main joy of being a king, because people are continually trying to divert him and provide him every kind of pleasure. A king is surrounded by people whose only thought is to divert him and stop him thinking about himself, because, king though he is, he becomes unhappy as soon as he thinks about himself…

So wretched is man that he would weary even without any cause for weariness from the peculiar state of his disposition; and so frivolous is he, that, though full of a thousand reasons for weariness, the least thing, such as playing billiards or hitting a ball, is sufficient to amuse him. (Pensees 139)

Pascal agrees with St. Augustine: the main cause of alienation is our own avoidance. We don’t want to attend to our inner life. As we have elevated our capacity for efficiency through technological innovation, we’ve simultaneously increased our capacity for diversion. No longer do men have to go to the sea or mountains, or even the billiard table to find distraction from the inner chamber of the heart. They just have to pull the screen out of their pocket. Soon, they won’t even need that. If the tech oligarchs have their way, you will only need a brain chip interface and diversion will be ubiquitous, never requiring the slightest movement.

As Pascal so brilliantly notices, it’s actually painful to follow the Socratic injunction to “know thyself.” There’s a reason the Athenians responded to Socrates, in so many words, “shut up and die.” But the long-term penalty of embracing diversion over self-knowledge is the inner pain of alienation. Diversion is always temporary. Even the king Pascal mentions eventually has to stand alone and look in the mirror, facing himself either to find peace or to shudder, alone.

This cultural trend towards diversion is the backdrop I think about when I wonder, “Why Write?” There are many good—and many vicious—reasons to write. Given this backdrop, though, I just want to expound on one reason amongst all these: the affirmation of my own humanity, and of yours.

In his recent YouTube video, “Why Write When You’ll Never be Published?”

wrestles with this same question. (Blake’s video essay is really beautiful. I recommend watching it and following his work.) He gives three reasons for writing.5Books have changed our lives.

Writing makes us sensitive to the world.

Writers love mucking around in words.

I really resonate with Blake as he talks about this—and that’s part of the point here. In watching Blake wrestle with this question, what’s on display is precisely his affirmation of his own humanity as a writer. At a certain point in the back third video, he spends some time teasing apart his own prose and talking about why he chose those particular words for his story, uncovering how they move him as the reader of his own writing. As Blake candidly lets the viewer into that process, and as he shares for us his own reasons for writing—whether or not anyone reads any of what he writes—we are allowed a moment of connection with Blake as he is clearly connecting with himself.6 This experience is one of seeing the author affirm his own humanity by refusing any longer to divert from his inner life, even as he invites us to join in and fully experience our own. It’s the simultaneous affirmation of his own humanity and of ours.

This is precisely why, as Blake says, books have changed our lives. When we read a good book, the prose is doing work, but it’s not just the beauty of the prose that’s changing us, it’s knowing that while beholding that beauty, we are in touch with the mind that crafted it. This is one reason why AI prose will never matter. It may be that GenAI will eventually be able to vomit up legitimately beautiful prose, but in reading it, none of us will be coming into contact with anyone. The experience of reading AI “writing” is essentially alienating. We come into contact with no one and humanity is necessarily denied. The majesty of being readers of real authors, on the other hand, is the way we can feel intimately close to authors we’ve never met in person, even authors who wrote thousands of years ago or with whom we share no life experiences.

George Saunders, contemporary American novelist, says something similar about reading:

I think that what any of us pays for when entering into a reading experience is that feeling of seeing another mind at work, and not in a rational way. There’s something thrilling about seeing this other mind at work in this blissful and private and self-referential way, and then suddenly your mind joins it. How weird and inexplicable that is. There’s a sort of knowledge that goes beyond our mundane everyday knowledge. The reader and writer are being smarter together than either one could be separately. This is like a sort of experiential proof of the fact that our apparent separation is delusional.7

In 20th century philosophy, a popular issue was the problem of other minds: something like, “How can I know that other beings have thoughts, feelings, and experiences like mine?” But older wisdom tells us no man is an island, and reading someone who is actively wrestling with their own thoughts, feelings, and experiences gives us not only the best answer we can get to that problem, it actually gives us robust access to those same thoughts, feelings, and experiences, even across vast gaps of space and time. How weird. How inexplicable, indeed.

Why write? People have always struggled with alienation, with the temptation to pull away from themselves, and from others. Writing is a door, back into the inner regions of the heart. It allows inner contact with one’s own heart and mind that is abnegated by diversion. In a mechanized world, it’s a door one can pass through to a living garden and leave open for others to follow.

In such a mechanized world, where everything is increasingly efficient and sleek, everything is also more fragmented. Efficiency requires the reduction of organic unities into their constituent parts, and the transformation of those parts into separate, discrete cogs in the larger machine. All of this fragmentation just makes the felt distance of separation from oneself and others worse.

This is only going to get worse. One of the main contributors to human alienation in my lifetime has been the establishment of the internet, and on the internet of social media in particular. Early on, as anyone alive at the time of the release of these technologies remembers, everyone expected the opposite. The belief of basically everyone was that these things would make us feel less fragmented and more unified. But they deny our embodied humanity, stoke our vices, and pit us against each other, tearing our souls apart at the seams. They were traps.

Now, Mark Zuckerberg says that AI will help cure loneliness.8 In fact, as anyone with any sense and any knowledge of the history of technology could tell you, AI will increase alienation. It will also undercut public trust in just about every form of media, including writing, since we will reach a point (if we haven’t already) of always wondering “Was that produced by AI or is it human?” AI is likely going to erode or even destroy the traditions of storytelling, debate, and development of ideas via image, video, text and other media that humans have developed over centuries.

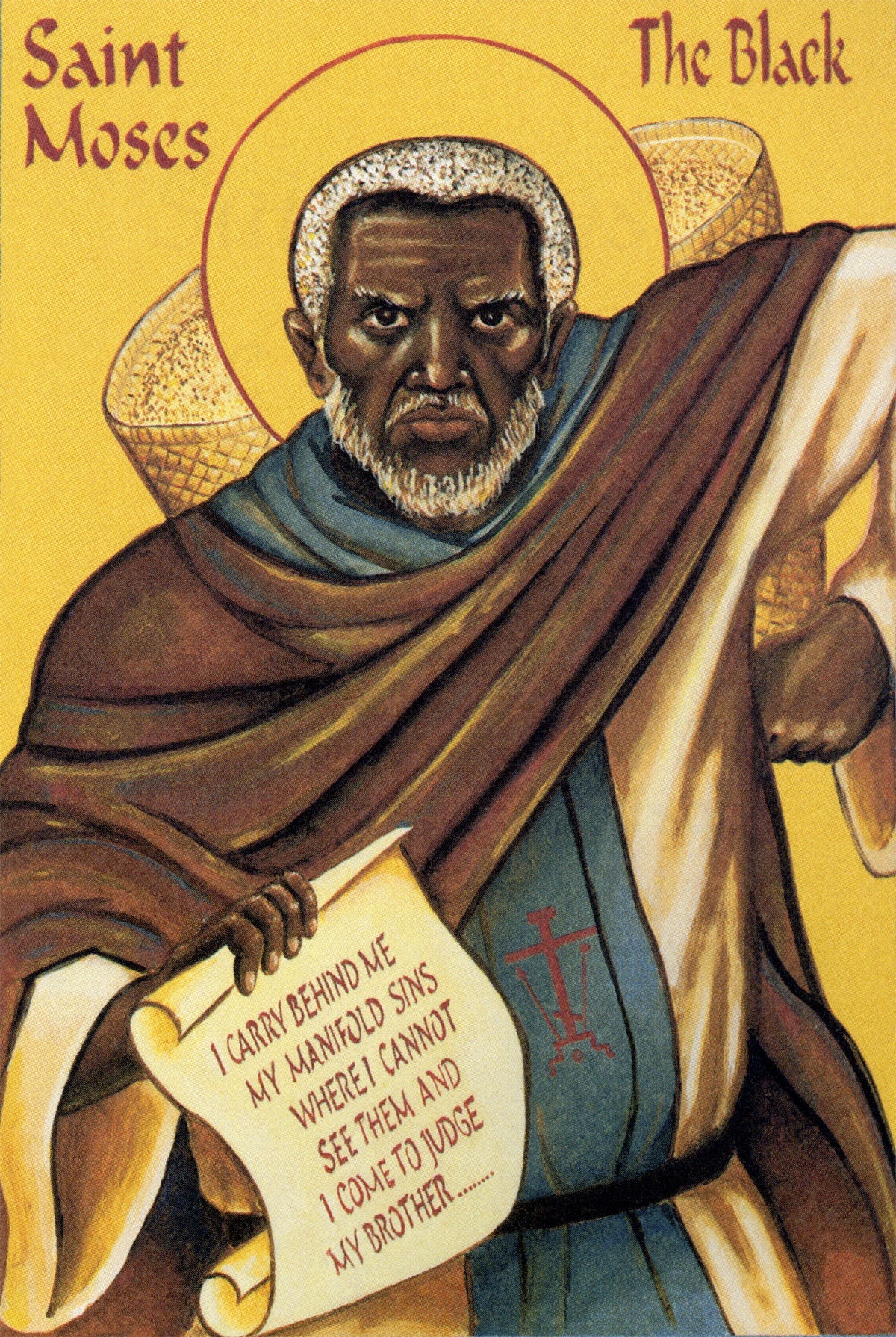

What is the point of writing, then, if readers won’t even be sure it’s me they’re encountering in my text? Why participate in a tradition that is being eroded and may not last? There is a story about the desert father, Saint Moses the Black, in which a brother came to Saint Moses looking for a word, essentially some morsel of wisdom on which to dwell and by which he might grow. Abba Moses told the brother, “Go, sit in your cell. Your cell will teach you everything you need to know.” At least part of what St. Moses was trying to teach this younger brother, I think, was a way of killing diversion. In the monastic context, the temptation to diversion arises because of the intensity of temptation one encounters embracing an ascetic life, along with (I assume) the extreme boredom. When you feel bored and tormented by your sins, you naturally want to look for something to distract you, to take you out of yourself. St. Moses’s advice? Don’t do it. Stay in your cell. You’ll learn something. You’ll have a real encounter with your own soul, with God, and potentially with one of those ineffable realities writers are always grasping at and trying to make accessible for themselves and others.

Saint Moses the Black wasn’t a writer. He was a penitent thief. But he was a wiser and better man that me, and he had the answer I think I’m struggling to articulate when I think about the value of writing. There’s no end to the opportunities to divert, automate, and delegate the cultivation of our humanity. The only way to refuse is to stay in our cell and work at something by which that cultivation can take place. Writing works pretty well.

I am a full time high school educator and parent. In order to do the writing I do here, I work on this publication between 4:00-5:00am most days. I write because I love to, and I won’t put a paywall up on my work. If you appreciate what you’ve read, it would encourage me if you left a note or shared it with a friend. If you’d like to show appreciation with monetary support, please consider giving to my church’s second building fund by clicking below, selecting “Give to Second Campus,” and entering an amount.

Actually, this did happen once, more than seven weeks after the accident and just a day or so after I wrote that. The fourth insurance adjuster I’m working with at my insurance agency, the one assigned to cover my own potential for liability, stopped for about a second to express her condolences. It really meant something. It also serves as the exception that proves the rule.

The NHTSA has estimated roughly 40,000 people dying in car accidents in the US in each of the last two years.

This lecture of Sartre’s is probably the easiest entry point into existentialism, and is fairly representative of the movement as a whole.

For a contemporary picture of the industrialist, just look at Marc Andreesen’s Techno Optimist Manifesto, or any “Effective Accelerationist” literature online.

His focus is on writing novels, but I think the question and his answers all apply to writing very generally.

I only realized after writing this paragraph that I was referring to Blake by his first name, and I take it that was induced in part by exactly the effect I’m discussing here: the way he lets us into his own intimacy with himself in his process. There’s a felt closeness between viewer and author there that makes one feel on a first-name basis.

Quoted in John Warner’s More than Words (2025), pp. 115-116.

https://mindmatters.ai/2025/05/zuckerberg-thinks-ai-can-help-cure-loneliness/

I’m so glad what I wrote could resonate with you, especially given what you’ve been through. Thanks for sharing your story.

Sorry for what you went through with that accident. That’s horrible! I can only imagine how hard that will hit emotionally and in so many other ways

Thanks for sharing Patrick. I really appreciate your perspective!